Learnings from the Museum of Fine Arts

September 4, 2025 · 9 min read

Yesterday, I had the distinct pleasure of visiting the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The place was really big and I didn't have time to explore all of it, but I will definitely be back soon :)

One of my favorite parts of visiting an art museum is how much culture and history you really get to witness; each art piece is a window into a soul, each selection of techniques reflecting upon values, traditions, and economic status of the society at the time. I love to speculate on what emotions were lingering behind each of the subjects' eyes. Some of them were infant heirs of noble positions. Were they bored? Were they scared of their parents' expectations, or of being stalked by hundreds of men eager to steal their ranking? Or, did they thrive in the spotlight, hungry to expand their parents' land into an empire?

First, I made my way to the Asian art gallery. Most of the prominent works on display were of funerary items. I saw reliefs, which were carved sculptures that project out of a flat background, furnishings and shrine offerings.

The Chinese conception of death shifted significantly throughout time. In the Qin and Han dynasty, highlighted by the First Emperor's terracotta army, elites filled tombs with vessels, spirit animals, murals, and reliefs to provide protection and blessings in the afterlife; these symbols revived themselves in the Tang because of the rise of Pure Land Buddhism, which presented a path for common folk to achieve rebirth in the Pure Land after death by chanting the name “Namo Amituofo”. Later, Neo-Confucianist ideals influenced the Song and Ming dynasties to shift their focus more towards moral responsibility.

This section of the frame (from the Northern Wei dynasty) might be found in a tomb. The depicted lion guardians are not natively found in China, but were often traded through the Silk Road. It is said that the Buddha's voice resembles the lion's roar.

The Northern Wei, having emerged from a nomadic steppe civilization, were a heavily militarized society built on a warrior elite. As Chinese culture moved into the Tang dynasty, relief panels more often began to document musicians, dancers, chariots, and banquets, which symbolized activities that the deceased hoped to continue in the afterlife. In the Song dynasty, Chinese culture further shifted away from exaggerated displays of power or moral lessons and into a more naturalistic lens.

Tombs would be coupled with epitaphs and illustrations, which detailed an individual's virtuous and dutiful deeds. An example is the above lintel, which showcases how a virtuous queen divested her jewelry to protest protest the king's behavior.

This shrine offering depicts "human symbols" for agility, wealth, power, which I personally found quite interesting and a departure from Buddhist ideals.

Large ears stems from Buddhist iconography: statues of the Buddha usually had elongated earlobes, a reference to his renouncement of worldly wealth by removing the heavy jewelry that stretched his ears. As such, they were a symbol of authority and wisdom.

In Buddhist statues and images, the eyes were traditionally left blank until a ritual known as "dotting the pupils" was performed, through which the statue would become animated with spiritual presence. Hence, many statues may have been unactivated, which is why they don't have pupils.

The Cosmological Buddha depicted above illustrates the view that every direction and age has its own Buddha, an eternal being that guides followers towards enlightenment. The Cosmological Buddha wears a monk's robe, known as a kāṣāya, and a necklace or other jewelry. Early Buddhism did not depict Buddha with such ornaments, but as Buddha's portrayal began to shift from a historical figure to a cosmic king, the pearls on his necklace became a symbol of his majesty.

A notable element of such panels is that often elements, including people, will melt into the background, creating a harmonious blur between subject and environment. This is done through the unifying use of swirls, which appear in wind, waves, beasts, and trees. These swirls represent qi, the vital energy that flows through everything.

In the corners of the painting, you'll notice small dragons. The conception of the dragon was not inspired by a single animal, but rather it is a composite of many: a deer's antlers, a snake's skin, etc. However, these animals are unified under the dragon's symbolism as a renewal of life: just as a deer changes feet and a snake sheds skin, the dragon highlights the cyclical nature of life. Phoenixes similarly originated as composites of multiple birds.

Finally, you can notice that lots of men had long, tied-up hair. This was to show filial piety: “Our body, hair, and skin are received from our parents; we must not injure or wound them.”

An interesting thing to notice is that many kings are shown as overweight, a symbol of their wealth, and generally women are portrayed with pronounced lips. In many dynasties, particularly the Tang, women used vivid lip colors to paint their lips much more fully.

An interesting thing to notice is that many kings are shown as overweight, a symbol of their wealth, and generally women are portrayed with pronounced lips. In many dynasties, particularly the Tang, women used vivid lip colors to paint their lips much more fully.

For many sculptures in antiquity, patrons would donate to add gold or other colors over time, as the sculptures changed hands, so it's quite difficult for museum restorers to remove all of the extra conditioning to return the art to its original form.

In the Han dynasty, a lot of the government's attention was focused on fighting nomadic powers, like Xiongnu, so horses become symbolic for strength and captured considerable focus in Han tombs.

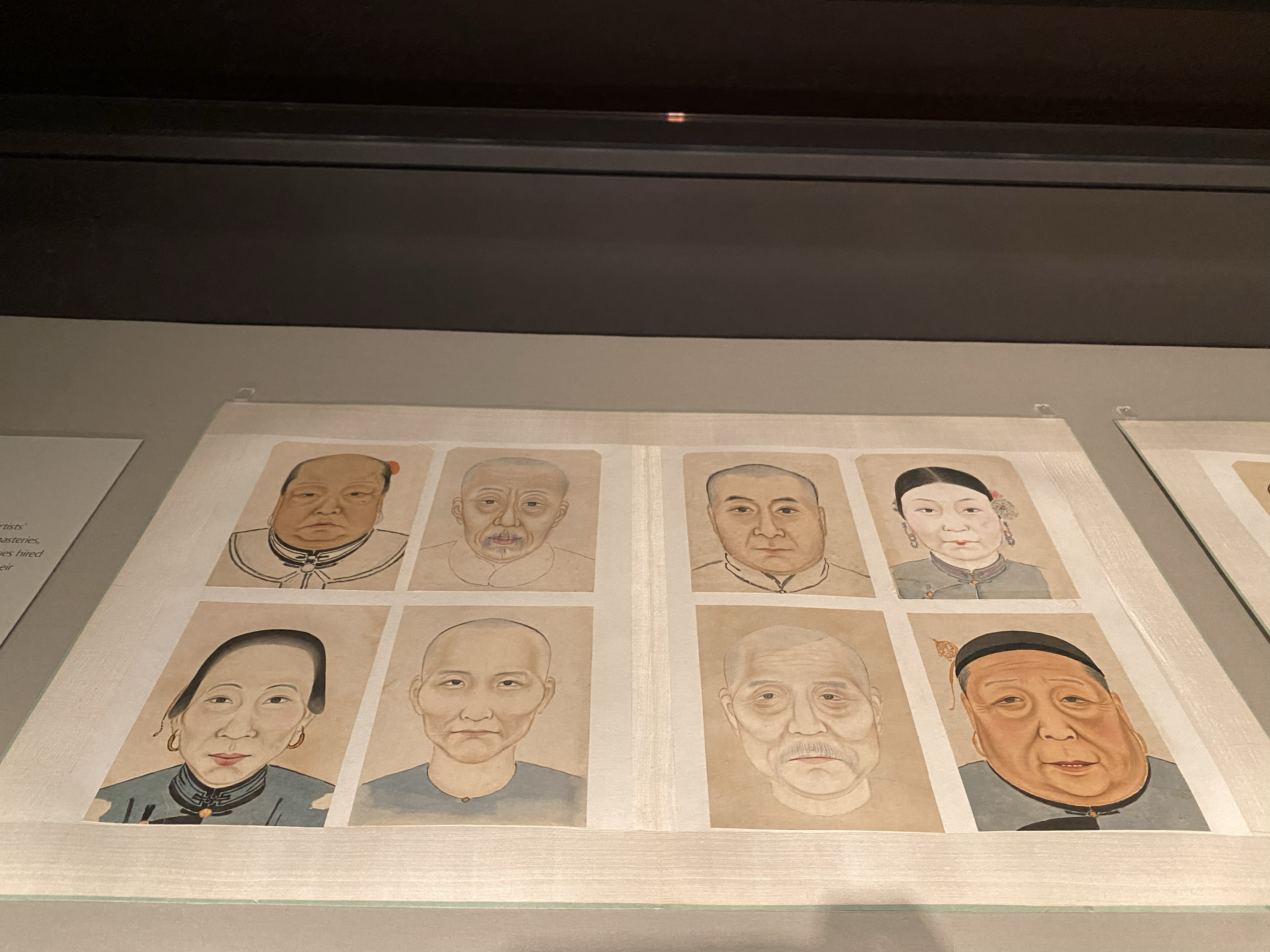

In the Song dynasty, families hung pictures like those above for the New Years, which showed multiple generations of a family. Note the aesthetic preference for perfectly symmetrical faces. Moreover, the artist carefully painted wrinkles, sagging skin, gray hair, and gauntness for some figures, showing that age was typically revered.

In the Song dynasty, silk and some ceramics were considered luxurious. Silks were typically displayed in monasteries, whereas paper was for personal use. An example of a luxurious porcelain is Ru ware, which had a bluish-green glaze and made out of fine, white stoneware clay with very little iron. This made its creation technically challenging, because the glazed tint typically comes from the iron in wood ash and clay oxide. Glazes are ground minerals in water, which includes silica (turns into glass at high temperatures), alumina (prevents the glaze from slipping off), and fluxes, which lower the melting temperature. The glaze slurry is applied, the piece is let to dry, and then fired at a high temperature in a kiln, specialized furnace. The level of oxygen was used to control the heat, which could be measured by the color of the flame.

Interestingly, currency coins, guan, cost more to make then their actual value. I learned that guan is different than bi, which just means disk. Bi are often made out of nephrite, a type of jade.

Then, I visited some of the European paintings. I've noticed that as a general trend, there are a lot more places to sit for European and American art than Chinese art. Purely speculating, I wonder if the museum interior designers intentionally selected this difference to better display the pieces in their natural habitats. Western oil paintings are often large and full of detail, which take time to fully soak in. Moreover, these pieces would likely be seen in grand chapels with art stretching to the ceiling, whereas Chinese art exists mostly in more intimate temples or studios. European oils also frequently display monks or saints grasping their heart in suffering, their eyes pointed towards heaven: perhaps the tall paintings are intended to evoke a similar response.

Another thing I've noticed is that European art uses far more contrast; of course, this is easier to do with oil than Chinese brushes, but I also wonder if it's because of cultural differences; many European paintings portray a black-and-white sense of justice, heroism, and grand victories, whereas Chinese art emphasizes naturalism and the meaning of small deeds. Stylistically, faces are more plush and plump, and artists use a lot of sharp colors like black, white, gold, red, and blue.

Another common theme in European oil paintings are heroic scenes of martyrs; for example, Saint Catherine, who survived a spiked breaking wheel, and Saint Sebastian, who was nursed back to health after surviving being tied to a tree and shot with arrows. Looking on, I'm filled with awe at the sheer will of people - Saint Sebastian, after that miracle, confronted the emperor again and was beaten to death for it. It's stories like these - an example in the modern day is Justo Gallego Martínez, who dedicated his life to building a cathedral - that makes me feel really small, in the same way that I feel really small when stargazing.

But, on the flip side, it's frightening how people could have come up with torture methods like a spiked breaking wheel. I can only imagine that they were raised with a lifetime of trauma, brought forth by powerful men who themselves were traumatized; the trace of hurt continuing forever.

Paintings of the wilderness, highlighting European exploration, are also prominent. European art is that of exploration, like the one above. Sometimes, I can't help but wonder if the painters feel lonely, though. But, maybe more likely, they grow used to the endless waves of wandering, the scaling of higher and higher peaks, as they venture farther and farther from home. I can't do much on the other side of the oil paint, but I wish them the best of luck as they march on, to where they were meant to be.